What if nature does not perfectly reflect its image in a mirror? The theory of parity challenges this symmetry that was believed

to be universal.

By Sacha Martin

On 10/20/2025 - 2 min of reading

For a long time, physicists believed that nature did not make a difference between left and right.

This idea of spatial symmetry seemed

obvious: whether it was gravitation, electromagnetism or nuclear forces, the laws of physics had to

remain identical in an inverted world.

Parity then embodied a fundamental

harmony, a vision of order and balance at the heart of science.

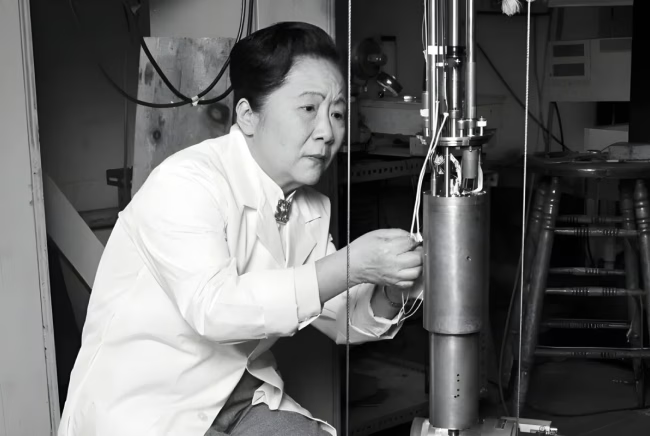

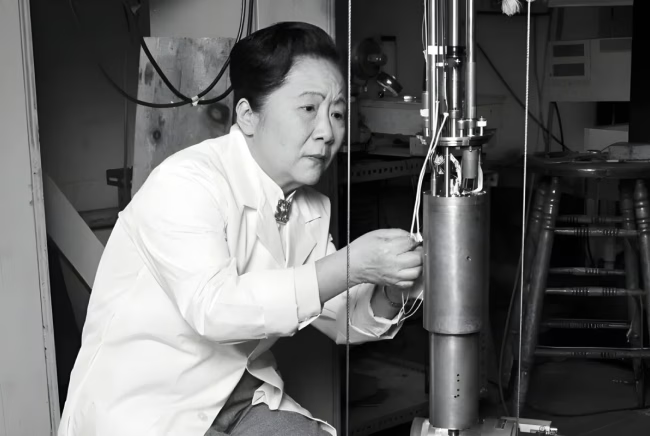

Shiung-Wu dog in full scientific experimentation, symbol of the women

who contributed decisively.

Shiung-Wu dog in full scientific experimentation, symbol of the women

who contributed decisively.

But in 1956, two Chinese theorists, Tsung-Dao Lee and Chen-Ning Yang, dared to question this

conviction. They proposed that the weak

nuclear force, responsible notably for beta decay, might not obey the conservation of parity.

To verify this bold idea, the physicist Chien-Shiung Wu conducted a historical experiment. Its

results were clear: in some interactions, nature violates parity.

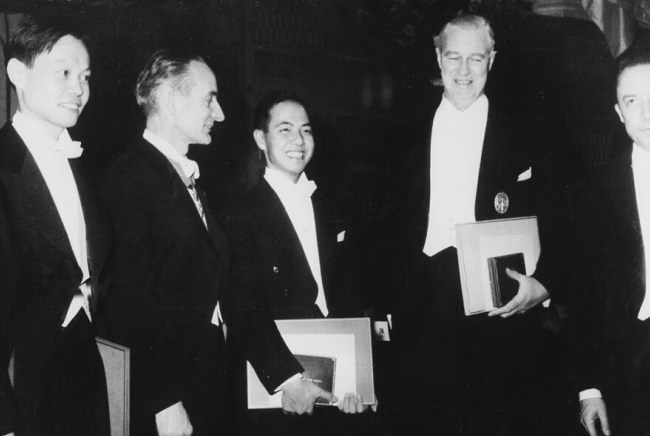

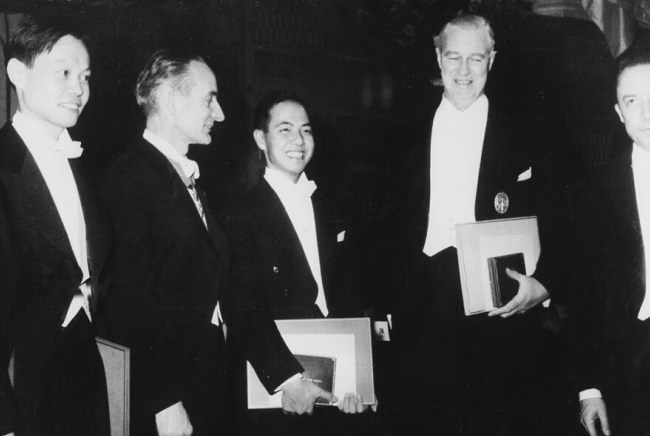

The male scientific team rewarded for the theory.

The male scientific team rewarded for the theory.

This discovery caused a real scientific upheaval. She revealed that the universe indeed

distinguishes left from right, breaking the idea of a perfect and universal symmetry. Parity, once a

symbol of order, became the sign of a fundamental asymmetry.

Even today, the violation of parity remains a major turning point in modern physics. It reminds us

that knowledge advances thanks to doubt, and that even the most established truths can be reversed

under the critical gaze of science.